Yesterday, in the late afternoon, as I was strolling through the Old City, the unmistakable booming rasp of Hasan Nasrallah, the Lebanese leader of Hezbollah, followed me from street to street. From the barber shops and the souvenir stores, the sweet shops and the scrap metal and screw store, even from the music store, the sound of his voice arose from small televisions or radios perched on sales counters, carrying through open doors, and turning the narrow stone streets in some kind of echo chamber.

The speech, Nasrallah's first public appearance since the summer's war, was broadcast from Beirut on all major Arab satellite news channels, as well as Syrian government channels, and, of course, the Hezbollah channel, Al-Manar.

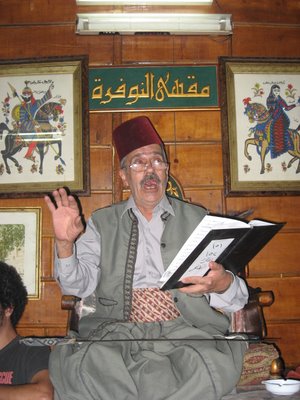

Not since this summer’s World Cup, had one televised event captured the nation, and perhaps not since the heady days of the pan-Arab movement of the 1950s and 60s, when the radio broadcast speeches of Gamal Abdel Nasser, the former Egyptian president, captivated the Arab street, has one Arab leader drawn such a popular following across the Arab world.

Arabs like anyone who stands up to Israel and they like a winner. Nasrallah represents both. He is praised for defending Arab land from invading Israeli troops, refusing to give up what they came for -- two captured soldiers -- and countering an Israeli bombardment with an unrelenting barrage of his own.

In most Arab countries there is a wide gap between street-level support for Nasrallah and the official view, which is muted. As a rule, guerrilla movements anywhere are enemies to long-serving Arab despots. Not in Syria, where the official view on most matters of international affairs mirror the Arab street. The bespectacled, black-turbaned Hasan Nasrallah, usually in a toothy grin, appears alongside images of the current and former Syrian presidents on posters in shop windows, in cut-outs in the front of busses and service vans, across the back windshields of cars. Hezbollah flags flutter alongside Syrian flags outside shops, from Sunni Muslim areas to Christian areas of Damascus. (Hezbollah is a Shiite party.)

The poster photographed above is on a pillar outside the Grand Mosque. From left, the current Syrian president, Bashar al-Asad, his father, the former Syrian president, Hafez al-Asad, and Nasrallah. The caption reads: “The victory for the resistance.”

I’m connected to the Internet at one of Damascus’ trendy Western-style coffee houses which offer free wireless Internet access. The chain, inhouse coffee -- all lowercase -- which has no Arabic spelling of its name in its signs or logos, boasts five locations around the city.

I’m connected to the Internet at one of Damascus’ trendy Western-style coffee houses which offer free wireless Internet access. The chain, inhouse coffee -- all lowercase -- which has no Arabic spelling of its name in its signs or logos, boasts five locations around the city.